At age 27, long before he would become the titan of Russian literature, Fyodor Dostoevsky was sentenced to four years of hard labor in Siberia for crimes against the state.

Before his deportation, he was given a leather-bound copy of the New Testament. In her memoirs, Dostoevsky’s wife, Anna Grigor’evna said that “During the entire four years of his imprisonment [Fyodor] never allowed himself to be parted from this holy book,” adding that “he used to say that the Gospel was the only thing that kept hope alive in his heart. Only in that book did he find support; whenever he resorted to it, he was filled with new energy and strength.” [Source: Geir Kjetsaa, Dostoevsky and His New Testament].

Dostoevsky made very few notes in the margins of the book, but one of the scriptures he did mark offers possible insight into what shaped his writing.

“No man hath seen God at any time. If we love one another, God dwelleth in us, and his love is perfected in us” (1 John 4:12).

After Dostoyevsky was released from prison, it seems that the deeper meaning of that scripture became the backbone of all of his later publications. For Dostoyevsky believed that we find the God as we love and serve others and as we are loved and served by them.

This idea of seeing the Savior in others is perfectly personified through the character Sonya from his novel Crime and Punishment.

|

| “Crime and Punishment” by Fyodor Dostoevsky |

Like the Savior, Sonya absorbs the hurt that people inflict upon themselves and others and labors to heal the wounded heart.

Sonya’s father, for example, is a drunk that has squandered almost all of his family’s fortune and income. Realizing that the family will die of starvation if something isn’t done Sonya gives herself up to prostitution to provide income for the family.

After returning home from her first appointment as a prostitute, Sonya “laid thirty roubles on the table before [her mother] in silence. She did not utter a word, she did not even look at her…and then I saw…I saw Katerina Ivanovna, in the same silence go up to Sonya’s little bed; she was on her knees all the evening kissing Sonya’s feet and would not get up” (Dostoevsky 14).

This expression of gratitude was echoed by Raskolnikov, who, after finding hope through her, also kisses her feet: “He put his two hands on her shoulders and looked straight into her tearful face…All at once he bent down quickly and dropping to the ground, and kissed her foot” (262).

These examples Sonya’s feet being kissed are allusions to Christ whose feet were also kissed, washed or bathed in the tears of his followers and worshipers. His followers did this because they saw in him both their temporal and spiritual salvation and they revered him for it.

Katerina kissed the feet of Sonya because Sonya provided a temporal salvation for her family (thirty rubles to feed her starving family) and Raskolnikov kissed Sonya’s foot because he saw spiritual salvation in her. Raskolnikov explained to Sonya that “I did not bow down to you, I bowed down to all the suffering of humanity” (262). In saying this, Raskolnikov made it clear that he saw a Savior in Sonya for he believed that she carried the weight of the world (“the suffering of humanity”) upon her.

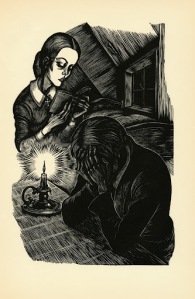

|

| Sonya reads to the murderer Raskolnikov |

Sonya’s Christ-like personality seems to have such a strong, heavenly effect on Raskolnikov, that whenever he is around her he finds his soul moving towards repentance. Literary critic, Richard L. Chapple, asserts that Raskolnikov seeks redemption “by submitting himself to civil prosecution under the influence of Sonya who hopes to lead him to a Christ-centered life” (Chapple, 95). After finding redemption in her and kissing her feet, Raskolnikov has a frank and honest conversation with Sonya about the realities of God and eventually pleads with her to read to him the story of Lazarus.

Her conviction of the truthfulness of the story is a turning point for Raskolnikov and his path to redemption: “And drawing a painful breath, Sonya read distinctly and forcibly as though she were making a public confession faith. ‘Yea, Lord: I believe that Thou art the Christ, the son of God Which should come into the world’” (266). While listening to this, Raskolnikov was no doubt in awe that despite being a prostitute, and enduring a painful and shameful situation, Sonya maintained a pure faith in Christ and continued to see the goodness of God.

Perhaps the greatest comfort given to Raskolnikov is when, after emphasizing that Lazarus had been dead for four days (it had been four days since Raskolnikov has committed murder) Sonya says this: “‘And he that was dead came forth.’ She read loudly, cold and trembling with ecstasy, as though she were seeing it before her eyes” (267). Her conviction and her faith in the promises of God is certainly pivotal for Raskolnikov, as it eventually moved him to repentance.

But apart from her willingness to absorb the sufferings of others and her ability to move souls to repentance, perhaps the Savior in Sonya’s most visible when she showed her love, compassion and commitment to help the sinner.

Shortly after Raskolnikov confesses his sins to Sonya, “She jumped up, seeming not to know what she was doing, and, wringing her hands, walked into the middle of the room; but, quickly went back and sat down again beside him, her shoulder almost touching his. All of a sudden she started as though she had been stabbed, uttered a cry and feel on her knees before him, she did not know why” (334). Naturally, one would expect her to shudder at the confession of such a terrible and horrible crime. Furthermore, one could not blame her if she fled from the room in terror.

But instead, something remarkable happens.

s her why she’s doing this. Sonya’s reply is simple and truthful: “There is no one–no one in the whole world now so unhappy as you!” Like Christ, Sonya recognizes the pain and suffering of the lowliest individual and seeks to alleviate it. She, having experienced great pain, has an enlarged heart, capable of great compassion.

But if this wasn’t enough to demonstrate how Sonya helps the sinner, Sonya steps beyond what a normal human could be expected it give in terms of compassion. Like Christ, Sonya offered to bear Raskolnikov’s pains with him. “‘I will follow you, I will follow you everywhere. Oh, my God! Oh, how miserable I am!…Why, why didn’t I know you before! Why didn’t you come before? Oh, dear!…Together, together!”’ she repeated as it were unconsciously, and she hugged him again. “I’ll follow you to Siberia!”’ (335).

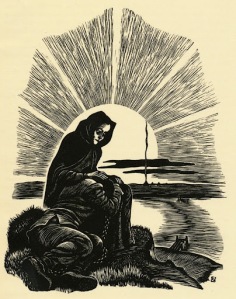

|

| Sonya comforts Raskolnikov in Siberia |

In Dostoevsky’s time, Siberia was known to be a place of extreme cold, prison camps and criminals—it was (if we take Dante’s description of a cold and frozen Hell seriously) a very real, physically tangible Hell. Dostoevsky himself had been imprisoned in Siberia for four years and it represented literal a Hell to him. Raskolnikov’s earthly punishment, therefore, is to go to an earthly hell. So when Sonya says that she is going to go with him to Siberia, she is essentially saying that she will go to hell and back with him.

Sonya’s Savior-like compassion runs deep. When Raskolnikov attempts to justify his murders he says “‘I’ve only killed a louse, Sonya, a useless, loathsome, harmful creature.’” To which Sonya incredulously replies: “‘A human being–a louse!’” (338). In seeing the compassion that Sonya has for even “a louse” Raskolnikov’s justifications for murder begin to dissolve and he soon openly confesses his wrongs: “‘Did I murder the old woman? I murdered myself, not her! I crushed myself once and for all, for ever!’” (341).

But Sonya’s compassion shines through his state of wretchedness. Her eyes fills with tears and she urges Raskolnikov to repent. “Suffer and expiate your sin by it, that’s what you must do” (342). After this and other pleadings on Sonya’s part, Raskolnikov eventually does confess his sin and after many years receives the redemption he seeks. “Sonya’s devotion to Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment ultimately turns his course from proud rebellion to concern and love for the individual, the first step toward a meaningful relationship with Jesus Christ” (Chapple, 96).

Like the Savior, Sonya extends a very personal and one-on-one offer of redemption. The symbolic and hidden nature of the Savior’s role in Crime and Punishment is reflective of the often obscure and hidden nature of heaven in our own lives. As Doestoevksy means for each of us to search for the Savior in his books, he also means for us to search for him in the scriptures and in our own lives.

“No man hath seen God at any time. If we love one another, God dwelleth in us, and his love is perfected in us” (1 John 4:12).

Works Cited Chapple, Richard L.. “A Catalogue of Suffering in the Works of Dostoevsky: His Christian Foundation.” The South Central Bulletin 43.4 (1983): 94-99. Print. Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. New York: International Collectors Library: 1993.

Comments are closed