Although separated by an ocean, several decades, and completely different audiences, it is remarkable how strikingly similar Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) are to one another.

In what ways are these two books so similar? More importantly, what is the primary message that these two authors—separated by geography, societies and history—are trying to convey about the human experience?

Quite simply, the experiences of the characters Tess and Hester are archetypal stories of redemption.

It is no surprise, then, that Hardy and Hawthorne’s masterpieces are so similar; for archetypes are reflections of greater, common themes of humanity. Through the lives and personalities of the main characters, Tess and Hester, the despicable deeds of the oppressive men in their lives, the cowardly character of their lovers, or the symbolic representations of their children, all of these things point to the overarching theme of redemption.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles and The Scarlet Letter

Published in 1891, Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles challenged many social issues in England by openly discussing sexual themes and gender issues. A young, impoverished English girl named Tess is raped by a nobleman, the result of which produced a bastard child that died shortly after birth. Tess’s attempts to move on with her life and achieve happiness prove demeaning and difficult until her public execution.

In The Scarlet Letter, published forty years prior to Hardy’s work, Nathaniel Hawthorne tells a story rich with religious symbolism and repentance. Set in seventeenth century Puritan Boston, Hester Prynne gives birth to an illegitimate child after committing adultery with the town minister, Arthur Dimmesdale. The narratation follows both of their lives until Hester is forgiven and Dimmesdale confesses.

Tess and Hester – Two Maids

The initial focus of conflict in Tess of the d’Urbervilles stems from Tess’s father, Mr. Durbeyfield, and his discovery of their once noble family line. This piece of information, idly tossed by a parishioner on horseback to the lazy peasant, directly affected the rest of Tess’s life. The impoverished family soon latched onto the idea of their once proud state and sought protection and financial security from a family that shared their noble name.

As a result of this new-found identity, Tess Durbeyfield was sent to work for the d’Urbervilles where she soon discovered that they were not true family relations, but merely wealthy people who had bought the practically deceased name of d’Urberville. From that moment on, Tess was tossed to and fro in a life of uncertainty and instability which eventually ends with her death.

But while Tess’s familial identity carried all of the weight in her story, Hester’s lineage held little to no weight of its own. She, like Tess, was a descendant of nobility. While recalling her life in England, Hester thought of “her paternal home; a decayed house of gray stone, with a poverty-stricken aspect, but retaining a half-obliterated shield of arms over the portal, in token of antique gentility” (Hawthorne 47). That simple sentence served as the first and last mention of Hester’s noble heritage—a heritage whose only resemblance to Tess’s was its decayed worth.

It is interesting to note that because the Durbeyfields had no knowledge of who they were as a family, they lashed out collectively and desperately for identity. Conversely, Hester Prynne knew exactly who she was and where she came from and with this knowledge she was able to hold herself with “perfect elegance…after the manner of the feminine gentility of those days; characterized by a certain state of dignity” (Hawthorne 50), even though the whole of her town was against her.

The two maidens shared innocence and naiveté that were illustrated, in-depth, within their respective stories. Two years

prior to Hester’s move to Boston, she lived in England where she had consented to marry a man much older and more intelligent than herself. When she pondered this anew nine years later, Hester “marveled how she could ever have been wrought upon to marry him!…and it seemed a fouler offense committed by Roger Chillingworth [her husband] than any which had since been done him, that, in the time when her heart knew no better, he had persuaded her to fancy herself happy by his side” (Hawthorne 154).

Tess’s innocence is notably marked at the beginning of the book: “Phases of her childhood lurked in her aspect still. As she walked along to-day, for all her bouncing handsome womanliness, you could sometimes see her twelfth year in her cheeks, or her ninth sparkling from her eyes; and even her fifth would fit over the curves of her mouth now and then” (Hardy 39).

With this innocence and naiveté imbued into their personalities and appearances, they became natural prey to colossal mistakes and had little foresight of the painful consequences that would follow.

In sinister scenes of similarity, both Hester and Tess had affairs with ministers. Arthur Dimmesdale was the unmarried pastor of Hester’s congregation and secretly fathered her child, Pearl.

In stark contrast to the consensual relationship of Hester and Arthur, Tess was raped by Alec d’Urberville. Years later, when Alec and Tess met once more, Alec had “converted” and was a traveling evangelical minister. Upon discovering Tess, Alec began to lust after her again, and playing on her concern for her family’s welfare, he lured her into his trap once more. After renouncing his evangelical dreams and promising financial security for Tess and her family, Alec was able to convert Tess into becoming a deceived mistress who played part in a heartless relationship.

In sight of these sins and frailties, the salvation of Tess and Hester (and Dimmesdale and Alec, for that matter) lay in the truth. Hester faces her moment of truth head on and with an air of pride that one would not expect under such circumstances. She admitted her follies to the townspeople and to herself which, in turn, granted her a kind of strength. In the end, it was said of her that “…the scarlet letter was her passport into regions where other women dared not tread. Shame, Despair, Solitude! These had been her teachers–stern and wild ones–and they had made her strong” (Hawthorne 174).

In the course of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Tess falls in love with and marries a man named Angel. Not long after their wedding ceremony, Angel confesses to having had a sexual relationship with a woman years earlier while living in London and asks for Tess’s forgiveness. She forgives Angel in abundance stating: “O, Angel — I am almost glad — because now you can forgive me!” (Hardy 230). She then reveals to Angel the forced relationship she had years earlier with Alec d’Urberville, a relationship that produced a sickly child that died shortly after birth.

In a stunning display of double standard, Angel replies that he cannot forgive her because “forgiveness does not apply to the case! You were one person; now you are another. My God—how can forgiveness meet such a grotesque—prestidigitation as that!” (Hardy 232). The love for Tess grown in Angel’s breast quickly evaporates and he impulsively leaves for Brazil, leaving Tess behind but assuring her that he would return some day. While writing to Angel, Tess thought to herself that “never in her life—she could swear it from the bottom of her soul—had she ever intended to do wrong; yet these hard judgments had come. Whatever her sins, they were not sins of intention, but of inadvertence, and why should she have been punished so persistently?” (Hardy 347).

But under these judgments and punishments, Tess was, day by day, growing stronger. Towards the end of her life she overcame Alec (the physical obstacle to her true happiness) and faced her own execution with boldness. Her free admission of her supposed sins and her lover’s willingness to be with her no matter the cost, offered her the redemption she had sought through the love of her own Angel. To the men who took her into custody she quietly and bravely said: “I am ready” (Hardy 382).

For Hester and Tess, there grew within each of them strength and courage that replaced their innocence and naiveté. Under the weight of their mistakes they blossomed from maidens into women and overcame their past.

For their male counterparts, however, the story is much different. Unlike Tess and Hester who lived with and accepted the shame of what had happened to them, Alec and Dimmesdale remained silent until death came for them both.

Alec and Dimmesdale – Saints and Sinners

As professed ministers and upper-class men, Alec and Dimmesdale are both masqueraders—men who live lives of hypocrisy and deceit.

Placed under the guise of supposed nobility, the reader is led to believe that Tess’s presumed, distant cousin, Alec, would not only be benevolent and sympathetic to the plight of his own kin, but that he would act in a kingly and virtuous manner towards the young woman, Tess. But in a sadistically sick twist of irony, Alec Stoke-d’Urberville not only subjects Tess to arduous labor but sexually pursues her until he eventually rapes the young girl, proving that Alec Stoke-d’Urberville was more animalistic and callous than his name and fame proclaimed him to be.

For Arthur Dimmesdale, the judgment is just as fierce. As the local parish, Dimmesdale’s role is to declare the gospel and denounce sin, but in absolute hypocrisy, Dimmesdale impregnates Hester Prynne, a married woman. For seven long years, Arthur keeps this tragic sin a secret, giving powerful, sorrowful sermons to his parishioners and despising himself more and more each day.

In another show of similarity, both Alec and Dimmesdale, despite their outward gestures of repentance and regret, return once more to their sinful ways.

Alec rediscovers Tess when she is most vulnerable and plays upon her weaknesses to have her to himself once more. In realizing this betrayal, Tess screams at Alec: “you had used your cruel persuasion upon me…you did not stop using it…my little sisters and my brothers and my mother’s needs—they were the things you moved me by…and you said my husband would never come back—never and you taunted me, and said what a simpleton I was to expect him!…and then he came back! Now he is gone…O yes, I have lost him now—again because of—you!” (Hardy 369).

In his deceptive deeds Alec proved that he is not as penitent nor converted as he wanted others to believe.

Likewise, upon meeting Hester Prynne in the woods, seven years after their moment of sinful passion, Arthur Dimmesdale began to confide his whole heart and soul to Hester until, at length, “they sat down…side by side, and hand clasped in hand” (Hawthorne 170) and they resumed a relationship they should never have started. By this physical token, one could rightly presume that the Minister was never truly repentant of the feelings he had for the married woman, but simply for the deed that became public.

In the end, the sins of both preachers catch up to them. To quote the Bible that both men frequently used in their sermons: “Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. For he that soweth to his flesh shall of the flesh reap corruption; but he that soweth to the Spirit shall of the Spirit reap life everlasting” (The Bible, KJV Galatians 6:7-8).

By the end of each book, both ministers receive the wages of their hypocritical service. Tess, at the height of her passion and epiphany, saw Alec for the true deceiver he was and she stabbed him through the heart.

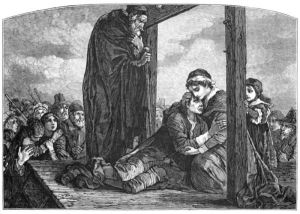

Arthur Dimmesdale, unable to contain himself any longer, confesses his sins upon the town scaffold and with “tremulous solemnity,” Dimmesdale tells Hester that “when we forgot our God—when we violated our reverence each for the other’s soul—it was thenceforth vain to hope that we could meet hereafter in an everlasting and pure reunion” (Hawthorne 222). He dies shortly after this sorrowful pronouncement.

The fates of both these men were fates that they had unknowingly selected through the laws they had violated. Through their study of man and religion they were aware, albeit somewhat dimly, of the hard road that surely lay before them. The conclusion of their hypocritical lives where physical and dramatic representations of the redemption of both Tess and Hester. For as Tess was released from oppression as she spilled the scarlet blood of Alec, Hester was released from the weight of the scarlet letter when Arthur Dimmesdale publicly confessed and died.

However, beyond anguish and sorrow of these men, there were two other men who were hurt as well—men who did nothing to provoke the pain but who were forced to pay a price nonetheless.

Angel and Chillingworth – Angels and Demons

Angel Clare and Roger Chillingworth found themselves in similar situations: they viewed themselves as victims. Roger Chillingworth felt like a victim because he was married to a young woman who broke her wedding vows by committing adultery and Angel Clare shared similar feelings because his wife had “violated” his culture’s sense of sexual propriety.

In this, Angel and Roger were both faced with a divine choice: do you forgive the person you love the most for doing something you loathe the most?

When Angel learns of Tess’s past, “his face…withered (Hardy 231)” and he denies her forgiveness. Shortly after that he flees to Brazil to farm and to escape his shock. Months later, when he returns: “You could see the skeleton behind the man, and almost the ghost behind the skeleton…his sunken eye-pits were of morbid hue, and the light in his eyes had waned. The angular hollows and lines of his aged ancestors had succeeded to their reign in his face twenty years before their time” (Hardy 357).

Apart from the change in his physical appearance, his spirituality or his views about Tess had changed as well. After reading a distressing letter from Tess, his mother replies, “Don’t, Angel, be so anxious about a mere child of the soil!” to which Angel replies,”Child of the soil! Well, we all are children of the soil!…her father is a descendant in the male line of one of the oldest Norman houses, like a good many others who lead obscure agricultural lives in our villages, and are dubbed ‘sons of the soil’” (Hardy 358).

His view and value of Tess had changed since his time in Brazil and he now felt to forgive. When the time came for him to lay all woe to waste, Angel takes his nobility a step further when he declares to Tess “I will not desert you! I will protect you by every means in my power, dearest love, whatever you may have done or not have done!” (Hardy 373).

As an aside, it is important to note that one of the foremost prevailing ironies of Tess of the d’Urbervilles is that those who value nobility—Jack Durbeyfield and Alec Stoke–d’Urberville—possess none. While Angel Clare—a man who detests old families and the mock sense of nobility that comes with it—possesses the most nobility at the close of the book.

Roger Chillingworth, however, parts from the peace that Angel experiences through forgiveness and opts to play God in his demand for justice. In his quest for revenge for the things that had happened to him, a demon-like change in Chillingworth becomes apparent.

A large number…affirmed that Roger Chillingworth’s aspect had undergone a remarkable change while he had dwelt in town, and especially since his time with Mr. Dimmesdale. “At first, his expression had been calm, meditative, scholar-like. Now, there was something ugly and evil in his face, which they had not previously noticed, and which grew still the more obvious to sight the oftener they looked upon him” (Hawthorne 112).

Chillingworth himself acknowledges this demonic metamorphosis to Hester: “Dost thou remember me? Was I not, though you might deem me cold, nevertheless a man thoughtful for others, craving little for himself…And what am I now?…I have already told thee what I am! A fiend!” (Hawthorne 151).

While Angel eventually learned how to pay the price of forgiveness, Chillingworth refused to relinquish his claim on the debt he believed was owed to him. Happiness, life and peace are restored to Angel through forgiveness and he was able to take a loving part in the redemption of Tess. But anger, revenge and torment consumed Roger Chillingworth because of his bitterness. Of him, Hawthorne wrote that within a year of Dimmesdale’s death he “positively withered up, shriveled away, and almost vanished from mortal sight” (Hawthorne 225).

Angel and Chillingworth were, like Alec and Dimmesdale, or Tess and Hester a mixture of saint and sinner—each of them carried a burden provoked by their own misdeed or lack of courage. But there were two other individuals who were wholly innocent—two children who did nothing to produce the pain, but served as the symbolic embodiments of it.

Sorrow and Pearl, Children of Great Price

Tess and Hester share a powerful similarity, one with highly symbolic overtures. Both characters, as a product of their sexual relations, give birth to illegitimate children. These children become children of great price for the tragic women. Tess named her son ‘Sorrow’ while Hester named her daughter ‘Pearl.’

Shortly after the birth of Sorrow, the baby grows gravely ill. Tess, wishing to have her child baptized, sends for the local parson, but her father denies the minister’s entrance. Tess cannot bear the thought of her child being damned, so during the night, she performs his baptism herself. The following morning, her child dies and she buries him in a neglected corner of the churchyard where God “Lets the nettles grow, and where all unbaptized infants, notorious drunkards, suicides, and others of the conjectural damned are laid. In spite of the untoward surroundings, however, Tess bravely made a little cross of two laths and a piece of string” (Hardy 116).

Sorrow served as a symbolic son to Tess. Doubtless, Tess named her child ‘Sorrow’ because he was the result an experience which had altered her life in a degrading and painful way. The idea was “suggested by a phrase in the book of Genesis” (Hardy 113) which states that God’s curse on women after the fall is to bring forth children in sorrow (see Genesis 3:16 and Hardy 113). The symbolic nature of Sorrow’s life reflects Tess’s own struggle in life and eventual rejection by religious authority (she is later known as an “adulterer” and a “murderer”). Her sin (of which Sorrow is a product) leads to her own death.

The opposite reflection of the boy Sorrow, Hester’s daughter Pearl did not die early in life. She instead served as a living symbol and reminder to her mother of the deed that Hester had done. Hester realized this early on when she fought the reflex to hold her three month old child in front of the scarlet ‘A’ on her chest, “wisely judging that one token of her shame would but poorly serve to hide another” (Hawthorne 50).

Hawthorne made the symbolic allusion unmistakable when he wrote that Pearl was “the scarlet letter in another form; the scarlet letter endowed with life!” (Hawthorne 90). Pearl was not passive in her silent preaching but continuously reminded Hester of her sin, being her living conscious until the end, when Dimmesdale confessed and the secrecy was revealed. “A spell was broken. The great scene of grief in which the wild infant bore a part, had developed all her sympathies; and as her tears fell upon her father’s cheek, they were the pledge that she would grow up amid human joy and sorrow, nor forever do battle with the world, but be a woman in it. Towards her mother, too, Pearl’s errand as a messenger of anguish was all fulfilled” (Hawthorne 222).

The children of Tess and Hester are not only parallel opposites of one another, but reciprocal reflections of their mothers. The boy Sorrow is sickly for the duration of his short life and dies, only after briefly having known what life was like. His baptism by his mother (an unorthodox and pagan practice) and his burial in an obscure corner of the church graveyard paint an allegory of Tess’s life. After a short bitter life, filled with poverty and heartache, Tess has brief encounters with light and life before offering herself up (at the pagan temple of Stonehenge) to be executed for murder. The tragedy of Sorrow’s life is a shadow of Tess’s redemption.

The girl Pearl lives a long, healthy life after fulfilling her role as a representation of Hester’s sin. The duration and fullness of her life is emblematic of the redemption of Hester after Dimmesdale’s confession and the discontinuance of her role as a living scarlet letter was further evidence of Hester’s newly gained purity and piety.

Redemption

Of the many comparisons that could be made between the two books, the prevailing parallel between Tess of the d’Urbervilles and The Scarlet Letter is redemption. At the conclusion of each book, Hester, Tess, Dimmesdale and Angel were finally able to stand before their oppressors and their persecutors with boldness. Hester stood upon the scaffold (the town symbol of broken religious laws and shame) with her lover, Arthur Dimmesdale while Tess stood upon the altar at Stonehenge (the pagan Temple of sacrifice) with her lover, Angel Clare. Both couples, after years of extremity and hardships were able to stand strong and confident after being purely and faithfully purged of their scarlet sins.

Works Cited

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Boston: Bedford Books, 1998.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. New York: Penguin Books,1983.

Comments are closed